Tracey Emin has a number of old scores to settle and, at least in the early days of her career as an artist, she made that more or less clear to the relevant parties.

With the launch of the 8mm and Super-8 film format in the 1960s, the industry of reproducible reality made one step further into the living room. Alongside the traditional slide shows documenting family celebrations and holidays, there was now the option of film. Convenient, easy-to-operate cameras, lightproof cassettes for the film material, a ready-addressed envelope in which to send the film away to be developed, and portable cutting and sound equipment for ambitious amateurs – all these accoutrements evened the path for video, the later mass medium.

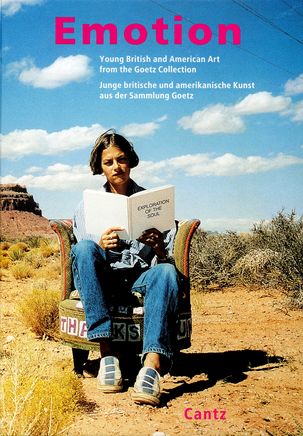

In her Super-8 film Why I Never Became a Dancer, Emin casually captures the atmosphere of that type of amateur holiday film: there is no artificial lighting, and the footage showing houses, streets and a beach remains slightly wobbly and blurred. The locations remain unspecific and uninformative; history and memories are filled in by the commentary.

Emin returns to the Margate of the late 1970s. She was born in that town in 1963, and spent her childhood and teenage years there. Already in Georgian and Victorian times, Margate was a popular seaside resort offering Londoners escape from the omnivorous city. Those able to afford the fare took a ferry down the Thames and disembarked directly on Margate piers.

Today, in summer, the town is a destination for those who cannot afford to go abroad. Londoners arrive at the weekends for cheap nights out in the pubs and discos. Those forced to live there would prefer to move.

Alongside the images, Emin relates how she grew up in Margate. She names the places where she passed her time, mentions the sex that she had with different men – in passing, as it were – at the age of eleven, thirteen. It was sex that often left her feeling bad, used, desolate and empty. That soon began to make her think less of, even despise, men – but also made her aware of the power it gave her over them. At some point, she takes command of her body in a way that does not involve placing it at the disposal of others: she swaps sex for dancing. She enters a disco-dancing competition. Her head is in the clouds. She sees herself reaching the national final, dreams of escaping from Margate. She is happy with herself and her body, but is brought back down to earth by frenetic choruses of “Slag, slag, slag” from the audience (whose members include many of the youths she has slept with in the past).

By 1995, Margate is a long way behind her. The memories and the injuries, however, are still fresh and she now intends to show those boys what is what. She is in London in a big studio overlooking the park. It is her space, and the music is playing. She dances. She is free. She is better than all the rest.

(Text by Rainald Schumacher in: fast forward. Media Art Sammlung Goetz, Hamburg 2003)

![[Translate to English:] © Isaac Julien Close up of a pair of black dancers: A man stands behind a woman and looks at her neck](/assets/sammlung-goetz/_processed_/9/f/csm_isaac-julien-three1996-99-sammlung-goetz-muenchen-2_98045aa43d.jpg)